遭禁作家的英文詩集打開西藏

文/自由亞洲電台,邵得廉(Dan Southerland)

译者:台湾懸鉤子

http://rosaceae.ti-da.net/e2368968.html

Radio Free Asia, 2008-09-30

Banned Writer Sheds Light on Tibet

自由亞洲電台的執行編輯,邵得廉(Dan Southerland)--西藏最有名的女作家,從共產黨的接班人,蛻變成一個強而有力的批評家。雖然她失去了工作,雖然她的博客遭到關閉,雖然常常受到監視,然而,唯色透過她的詩,顯示了她說出真相的勇氣。

華府電/「最重要的,我祝妳有勇氣,」美國詩人潘布朗(Pam Brown)數十年前寫給她的女兒的祝語,「這樣,就會解決其他的每件事了。」

勇氣,就是西藏當代詩人唯色的生活與作品的主要特色。

一位在中國內部被禁的作家,唯色--藏語意謂著光芒--持續不懈地在她的北京小公寓裏寫作,寫下來的不僅是詩歌,還有散文,以及關於現在西藏情勢的報告。

她仍然常常受到中國警察的監視。

中國當局在今年三月西藏反對他們統治的起義之後,封鎖了西藏。武警現在已經有效地將西藏抗議之聲給噤住了。

但四十二歲的唯色,仍然還在言說,還在她的海外博客上,繼續發表文章與詩歌。

強而有力的批評人

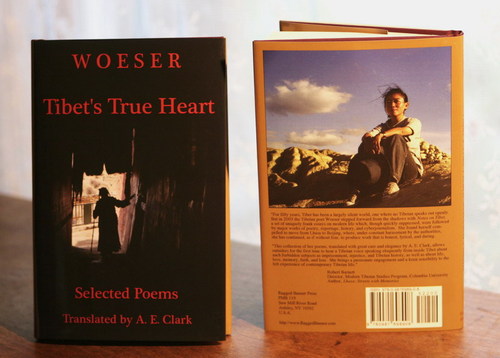

唯色的許多詩文,本來以中文創作的,現在已經集結以英文出版,詩集的英文標題是Tibet's True Heart(《西藏的真心》), 出版社是Ragged Banner Press。

由A.E. Clark很有技巧地翻譯成英文的詩集,刻畫出唯色從中國特權菁英的一份子,漸漸轉變成為一個強而有力的批評家的過程。她的詩讓讀者窺見到,不同於她散文的理性的另外感性面。

四年前,她面臨必須接受「政治錯誤」的「再教育」,決定離開文學雜誌的編輯工作,從拉薩搬到北京。接下來,她就被正式解僱了。

她的書《西藏筆記》曾經提到藏人對達賴喇嘛不渝的尊敬,卻是被政府當局辱罵為「分裂份子」、想尋求西藏獨立的惡人。

在2006年,她在當時的博客上貼出這位西藏精神領袖的照片,再加上一首祝他長壽的詩,她的博客就被關閉了。

唯色現在正在為政府不發給她護照,而提出官司。她預期不會贏。然而,就像她對美聯社所說的,她想要利用這個議題,「作為一個可以談論藏人多年來受到不公平對待的機會」。

奧運期間,在拉薩,警方盤問了唯色八小時,指控她拍攝警察與軍隊駐點的照片。她被迫必須刪除她的照片。

「我的信仰……就是驅策我寫作的力量」

身高大約五英呎多,講話輕柔,唯色在2006年接受自由亞洲電台採訪時說,她不會停止創作的。

「雖然我的博客被關了,」她說,「他們不能停止我的言說與寫作。」

「我的信仰以及對佛教的愛,大概是驅策我寫作的力量。當我在拉薩的單位裏工作時,我的薪水很不錯。但我從未感到自由,而那一點讓我感到困擾……我被解僱,這個事件反而讓我可以在作品裏自由表達自己。」

唯色在詩中想像過去,她描寫一個已經失落的西藏--擁有不受破壞的高山、不受打擾的寺院。然後她帶給我們西藏的即時圖像,與中國官方描寫的載歌載舞、渴求消費商品的藏人形象大相逕庭。

在她的詩「往昔」之中,唯色渴望一個受到神明護祐、山頂積雪、經幡飄飄的西藏:

往昔,往昔,怎樣的往昔

眾神守護著我們的家園

像喇嘛守護著心靈

像獒犬守護著帳房

但今天,眾神已遠去

眾神已遠去……

瞭解她的詩

不瞭解藏傳佛教的人可能會覺得唯色的詩很難懂。

幸運的是,翻譯者A.E. Clark在書末提供了45頁的註釋。讀者從中會瞭解,什麼時候一隻神鷹象徵的是達賴喇嘛,什麼時候一個諷刺的評語是指涉中國的電影種類。

但有的時候,她的詩令人驚訝地直言不諱。

在"西藏的秘密"一詩中,唯色將閱讀班旦加措的傳記(一位坐牢三十三年的僧人),比擬成「看見雪域的眾生被外來的鐵蹄踩成齏粉。」

在這首長詩之中,唯色描寫了一些政治犯所遭受的折磨,包括十四位「歌尼」,她們在獄中創作監獄生活的歌曲,然後用偷偷運到獄中的錄音機錄製。

其中一位女尼被關押時,只有十二歲,而關於這一位阿尼,她這樣寫道:「我僅僅在想,那囚牢裡,才十多歲的阿尼為何不畏懼?」

重新發現西藏

而「混血兒」一詩總結了唯色從菁英的女兒變成一個重新發現她的根的批評家的旅程。

她描寫「那一夜青春散盡的背叛」裏,「熱淚」讓她改變了原來的立場。

在Tibet's True Heart(《西藏的真心》)一書的前言之中,A.E. Clark為讀者提供了有用的背景介紹。

作為解放軍高階將領的女兒,唯色從小被教導「舊西藏是黑暗落後的」,而人民解放軍在1950年入侵西藏後,帶來了比較好的生活。

但是當她追尋西藏的文化時,唯色感覺到她受到佛教的吸引,但「她小時候對佛教是一無所知的」。然後她發現了她出生那一年爆發的文化大革命,很大程度地摧毀了佛教的文化。

唯色也發現她的父親,一個人民解放軍的軍官,卻是秘密佛教徒。她記得1980年代的某一天,在她的父母家裏,看到她父親身穿軍裝,「在班禪喇嘛面前單膝跪下」(當時人在西藏、最受藏人尊敬的精神領袖),她所感到的驚訝之情。

稍後, Clark寫道,唯色「才知道她父親,以她母親健康為名義,在漢地的一些佛教聖地所進行的旅行,都像是朝聖之旅。」

當唯色上個月被迫離開西藏的首都時,她寫了一首關於拉薩軍警無處不在、令人恐懼的詩,「拉薩的恐懼令我心碎,容我寫下」。

當她把這首詩貼在她的博客上,結尾時她加上了一句話:

「你有槍,我有筆。」

http://www.rfa.org/english/news/woeser-09302008132134.html

Banned Writer Sheds Light on Tibet

2008-09-30

By Dan Southerland, RFA Executive Editor—Tibet's best-known female writer has evolved from a member of China's privileged elite into a forceful critic. Despite the loss of her job, the closure of her blogs, and constant surveillance, Woeser reveals through her poems the courage to speak out.

WASHINGTON—“Most of all I wish you courage,” the American poet Pam Brown wrote to her daughter decades ago. “That usually takes care of everything else.”

Courage is a defining trait in the life and work of the contemporary Tibetan poet Woeser.

A banned author inside China, Woeser—the name means Rays of Light in Tibetan—continues to write from her small apartment in Beijing not only poems, but also essays and reports on the current situation in Tibet.

She is under constant Chinese police surveillance.

Chinese authorities locked down Tibet following a major uprising against their rule that began in early March. Paramilitary police have now silenced the voices of protest in Tibet.

But Woeser, 42, still speaks out, publishing essays and poems on a blog hosted abroad.

Forceful critic

Many of Woeser’s poems, written in Chinese, are now available in English in a book titled Tibet’s True Heart, from Ragged Banner Press.

Ably translated into English by A. E. Clark, the poems trace Woeser’s evolution from a member of China’s privileged elite into a forceful critic. Her poems provide an emotional counterpart to the dispassionate reason of her prose.

Four years ago, Woeser left her job editing a literary magazine in Lhasa and moved to Beijing when she faced “re-education” for “political errors.” Formal dismissal followed.

Her book Tibet Journal had mentioned Tibetans’ abiding reverence for the Dalai Lama, whom the authorities revile as a “splittist” seeking Tibetan independence.

In 2006, after she posted a photo of the Tibetan spiritual leader with a poem wishing him long life, her blogs were shut down.

Woeser is now suing the Chinese government for denying her a passport. She doesn’t expect to win. But, as she told the Associated Press, she is using the issue as “an opportunity to talk about the unfair treatment of Tibetans over the years.”

In Lhasa during the Olympics, police questioned Woeser for eight hours, accusing her of taking pictures of police and army posts. She was forced to delete her photographs.

‘My faith …led me to write’

Barely five feet tall and soft-spoken, Woeser said in a 2006 interview with Radio Free Asia that she will never stop writing.

“Though my blogs are shut down,” she said, “they cannot stop my speech and my writing.”

“My faith in religion and love for Buddhism largely led me to write. While I was working in an office in Lhasa, I was paid well. But I never felt free, and it bothered me… When I was fired from the job, the incident led me to freedom to express myself in writing.”

Envisioning the past in her poems, Woeser evokes a lost Tibet of undisturbed mountains and monasteries. Then she brings us up to date with images that clash with China’s official depiction of Tibetans as singing, dancing natives hungering for consumer goods.

In her poem “The Past,” Woeser yearns for a Tibet of snow-clad mountains and fluttering prayer flags under divine protection:

The past, the past… such a past!

A host of divinities sheltered our homeland

As a lama keeps watch over souls,

As a mastiff stands guard by the tent.

But the host of divinities is long gone, now,

The host of divinities is long gone.

Understanding the poems

Readers unversed in Tibetan Buddhism will find some of Woeser’s poems challenging.

Fortunately, translator A. E. Clark provides 45 pages of notes at the end of the book. One learns when an eagle symbolizes the Dalai Lama, or when a sarcastic remark alludes to Chinese genre movies.

But sometimes the poems are amazingly direct.

In “Tibet’s Secret,” Woeser likens reading the memoir of Palden Gyatso, a monk who served 33 years in prison, to “watching the creatures of the Land of Snow trampled to dust by foreign jackboots.”

In this long poem, Woeser describes the ordeals of a number of political prisoners, including 14 “singing nuns” who composed songs about prison life and recorded them with a smuggled tape recorder.

Of these nuns, one jailed at age 12, she writes: “I am only wondering why the nuns in that prison, mere teenagers, are not afraid.”

Rediscovering Tibet

The poem “Of Mixed Race” sums up Woeser’s journey from a daughter of the elite to a critic who has rediscovered her roots.

She describes a “a night of rebellion at the close of her youth” in which “hot tears” annul her earlier stance.

In the preface to Tibet’s True Heart, A. E. Clark provides the reader with useful background.

As the daughter of a senior Chinese army commander, Woeser had been taught that “the old Tibet was dark and backward,” and that when the People’s Liberation Army invaded Tibet in 1950, it brought a better life.

But as she explored Tibetan culture, Woeser found herself attracted to Buddhism, “of which she had known virtually nothing in childhood.” She then discovered that China’s Cultural Revolution, which exploded in the year of her birth, had done much to destroy that culture.

Woeser also discovered that her father, the PLA commander, was a closet Buddhist. She remembers her astonishment one day at her parents’ home in the 1980s at seeing him in full military dress go “down on one knee before the Panchen Lama,” the most revered spiritual leader then remaining in Tibet.

Later, Clark notes, Woeser “realized that trips on which her father had taken her mother, ostensibly for her health, had all been pilgrimages.”

When Woeser was forced to leave the Tibetan capital last month, she wrote a chilling poem about the intimidating presence of troops and police there, “The Fear in Lhasa.”

When she posted the poem on her blog, she added a parting shot:

“You have the guns. I have a pen.”

Comments